Paris-Roubaix

Paris-Roubaix is a one-day professional bicycle road race in northern France from Compiègne to Roubaix, near the Belgian frontier. Famous for rough terrain and cobblestones, it is one of the 'Monuments' or Classics of the European calendar. It has been called the The Hell of the North, A Sunday in Hell, Queen of the Classics or La Pascale: the Easter race. The race is organised by the media group Amaury Sport Organisation annually in mid-April.

History

Paris-Roubaix is one of the oldest races of professional road cycling. It was run first in 1896 and has stopped only for two world wars. It was created by two Roubaix textile manufacturers, Théodore Vienne (born 28 July 1864) and Maurice Perez. They had been behind the building of a velodrome on 46,000 square metres at the corner of the rue Verte and the route d'Hempempont. It opened on 9 June 1895.

Vienne and Perez held several meetings on the track, one including the first appearance in France by the American sprinter Major Taylor, then looked for further ideas. In February 1896 they hit on holding a race from Paris to their track. It gave them two problems. The first was that the biggest races started or ended in Paris and that Roubaix would be seen as too provincial a destination. The second was that they could organise the start or the finish but not both.

They spoke to Louis Minart, the editor of Le Vélo, the only daily sports paper. Minart was enthusiastic but said the decision of whether the paper would run the start and provide publicity belonged to the director, Paul Rousseau. Minart may also have suggested an indirect approach because the mill owners recommended their race not on its own merits but as preparation for another. They wrote:

Dear M. Rousseau, Bordeaux-Paris is approaching and this great annual event which has done so much to promote cycling has given us an idea. What would you think of a training race which preceded Bordeaux-Paris by four weeks? The distance between Paris and Roubaix is roughly 280km, so it would be child's play for the future participants of Bordeaux-Paris. The finish would take place at the Roubaix vélodrome after several laps of the track. Everyone would be assured of an enthusiastic welcome as most of our citizens have never had the privilege of seeing the spectacle of a major road race and we count on enough friends to believe that Roubaix is truly a hospitable town. As prizes we already have subscribed to a first prize of 1,000 francs in the name of the Roubaix velodrome and we will be busy establishing a generous prize list which will be to the satisfaction of all. But for the moment, can we count on the patronage of Le Vélo and on your support for organising the start?

The first prize represented seven months' wages for a miner at the time.

Rousseau was enthusiastic and sent his cycling editor, Victor Breyer, to find a route. Breyer travelled to Amiens in a Panhard driven by his colleague, Paul Meyan. The following morning Breyer - later deputy organiser of the Tour de France and a leading official of the Union Cycliste Internationale - continued by bike. The wind blew, the rain fell and the temperature dropped. Breyer reached Roubaix filthy and exhausted after a day of riding in disjointed cobbles. He swore he would send a telegram to Minart urging him to drop the idea, saying it was dangerous to send a race the way he had just ridden. But that evening a meal and drinks with the team from Roubaix changed his mind.

Easter mystery

Vienne and Perez scheduled their race for Easter Sunday. The Church objected. Riders would not have time to attend mass and spectators might not bother to try. Tracts were distributed in Roubaix decrying the venture. What happened next is uncertain. Legend says that Vienne and Perez promised the church that a mass would be said for the riders in a chapel 200m from the start, in the boulevard Maillot. The story is repeated by Pascal Sergent, the historian of the race, and by Pierre Chany, historian of the sport in general. Sergent goes as far as saying that Victor Breyer, whom he says was there, said the service was cancelled because 4am was too early. Neither mentions if the date of the race was subsequently changed.

However, the first Paris-Roubaix, Sergent says, was on 19 April 1896. But Easter Sunday in 1896 was two weeks earlier. The first Paris-Roubaix on Easter Sunday was the following year, 1897.

The first race

News of Breyer's ride to Roubaix may have spread. Half those who entered did not turn up at the Brassérie de l'Espérance, the race headquarters. Those who dropped out included Henri Desgrange, a prominent track rider who went on to organise the Tour de France. The starters did include Maurice Garin, winner of Desgrange's first Tour, who was the local hope in Roubaix because he and two brothers had opened a cycle shop in the boulevard de Paris the previous year.

Garin came third, 15 minutes behind Josef Fischer, the only German to have won. Only four finished within an hour. Garin would have come second had he not been knocked over by a crash between two tandems, one of them ridden by his pacers. Garin "finished exhausted and Dr Butrille was obliged to attend the man who had been run over by two machines," said Sergent. He won the following year, beating the Dutchman Mathieu Cordang in the last two kilometres of the velodrome at Roubaix. In 2004 Les Amis de Paris-Roubaix marked Garin's victories in the Paris-Roubaix event by placing a cobblestone - traditional trophy for winners of the race, on his grave. Sergent said:

As the two champions appeared they were greeted by a frenzy of excitement and everyone was on their feet to acclaim the two heroes. It was difficult to recognise them. Garin was first, followed by the mud-soaked figure of Cordang. Suddenly, to the stupefaction of everyone, Cordang slipped and fell on the velodrome's cement surface. Garin could not believe his luck. By the time Cordang was back on his bike, he had lost 100 metres. There remained six laps to cover. Two miserable kilometres in which to catch Garin. The crowd held its breath as they watched the incredible pursuit match. The bell rang out. One lap, there remained one lap. 333 metres for Garin, who had a lead of 30 metres on the Batave.

A classic victory was within his grasp but he could almost feel his adversary's breath on his neck. Somehow Garin held on to his lead of two metres, two little metres for a legendary victory. The stands exploded and the ovation united the two men. Garin exulted under the cheers of the crowd. Cordang cried bitter tears of disappointment.

Hell of the North

The race usually leaves riders caked in mud and grit, from the cobbled roads and rutted tracks of northern France's former coal-mining region. However, this is not how this race earned the name l'enfer du Nord, or Hell of the North. The term was used to describe the route of the race after World War I. Organisers and journalists set off from Paris in 1919 to see how much of the route had survived four years of shelling and trench warfare. Procycling

They knew little of the permanent effects of the war. Nine million had died and France lost more than any. But, as elsewhere, news was scant. Who even knew if there was still a road to Roubaix? If Roubaix was still there? The car of organisers and journalists made its way along the route those first riders had gone. And at first all looked well. There was destruction and there was poverty and there was a strange shortage of men. But France had survived. But then, as they neared the north, the air began to reek of broken drains, raw sewage and the stench of rotting cattle. Trees which had begun to look forward to spring became instead blackened, ragged stumps, their twisted branches pushed to the sky like the crippled arms of a dying man. Everywhere was mud. Nobody knows who first described it as 'hell', but there was no better word. And that's how it appeared next day in the papers: that little party had seen 'the hell of the north.'

The words in L'Auto were:

We enter into the centre of the battlefield. There's not a tree, everything is flattened! Not a square metre that has not been hurled upside down. There's one shell hole after another. The only things that stand out in this churned earth are the crosses with their ribbons in blue, white and red. It is hell!

"This wasn't a race. It was a pilgrimage.|Henri Pélissier, speaking of his 1919 victory.

History of the cobbles

Seeking cobbles is relatively recent. It began at the same time in Paris-Roubaix and the Ronde van Vlaanderen, when widespread improvements to roads after the second world war brought realisation that the character of both races were changing. Until then the race had been over cobbles not because they were bad but because that was how roads were made. André Mahé, who won in 1948 (see below Controversies), said:

After the war, of course, the roads were all bad. There were cobbles from the moment you left Paris, or Senlis where we started in those days. There'd be stretches of surfaced roads and often there'd be a cycle path or a pavement [sidewalk] and sometimes a thin stretch of something smoother. But you never knew where was best to ride and you were for ever switching about. You could jump your bike up on to a pavement but that got harder the more tired you got. Then you'd get your front wheel up but not your back wheel. That happened to me. And then you'd go sprawling, of course, and you could bring other riders down. Or they'd fall off and bring you down with them. And the cycle paths were often just compressed cinders, which got soft in the rain and got churned up by so many riders using them and then you got stuck and you lost your balance. And come what may, you got covered in coal dust and other muck. No, it's all changed and you can't compare then and now.

The coming of live television prompted mayors along the route to surface their cobbled roads for fear the rest of France would see them as backward and not invest in the region. Albert Bouvet, the organiser, said: "If things don't change, we'll soon be calling it Paris-Valenciennes," reference to a flat race on good roads that often ends in a mass sprint. L'Équipe said: "The riders don't deserve that." Its editor, Jacques Goddet, called Paris-Roubaix "the last great madness of cycling." Bouvet and Jean-Claude Vallaeys formed Les Amis de Paris Roubaix (see below). Its president, Alain Bernard, led enthusiasts to look for and sometimes maintain obscure cobbled paths. He said:

"Until the war, Paris-Roubaix was all on routes nationales. But many of those were cobbled, which was the spirit of the race, and the riders used to try to ride the cycle paths, if there were any. So Paris-Roubaix has always been on pavé, because pavé was what the roads were made of. Then in 1967 things began to change. There was less pavé than there had been. And so from 1967 the course started moving to the east to use the cobbles that remained there. And then those cobbles began to disappear as well and we feared that Bouvet's predictions were going to come true. That's when we started going out looking for old tracks and abandoned roads that didn't show up on our maps.

In the 1970s, the race only had to go through a village for the mayor to order the road to be surfaced. Pierre Mauroy, when he was mayor of Lille [Roubaix is virtually a suburb of Lille], said he wanted nothing to do with the race and that he'd do nothing to help it. A few years ago, there was barely a village or an area that wanted anything to do with us. If Paris-Roubaix came their way, they felt they were shamed because we were exposing their bad roads. They went out and surfaced them, did all they could to obstruct us. Now they can't get enough of us. I have mayors ringing me to say they've found another stretch of cobbles and would we like to use them.|Alain Bernard, President of 'Les Amis de Paris-Roubaix', 2007.

It was Alain Bernard who found one of the race's most significant cobbled stretches, the Carrefour de l'Arbre. He was out on a Sunday ride, turned off the main road to see what was there and found the last bad cobbles before the finish. It is a bleak area with just a bar by the crossroads. Bernard said: "Until then, it [the bar ('Cafe de l'Arbre')] was open only one day a year. In France, a bar has to open one day a year to keep its licence. That's all it did, because it's out in the middle of nowhere and nobody went there to drink any more. With the fame that the race brought it, it's now open all year and a busy restaurant as well."|Alain Bernard, President of 'Les Amis de Paris-Roubaix', 2007.

The Amis de Paris-Roubaix spend €10-15,000 a year on restoring and rebuilding cobbles. The Amis supply the sand and other material and the repairs are made as training by students from horticulture schools at Dunkirk, Lomme, Raismes and Douai. Each section costs €4-6,000, paid for equally by the Amis, the organisers and the local commune. Bernard said:

"The trouble is that the Belgians then come out to see the race and they pull up a cobble stone each and take it home as a souvenir. They've even gone off with the milestones. It's a real headache. But I'm confident now that Paris-Roubaix is safe, that it will always be the race it has always been."|Alain Bernard, President of 'Les Amis de Paris-Roubaix', 2007.

Strategic places of historic races

The strategic places where earlier races could be won or lost include Doullens Hill, Arras, Carvin and the Wattignies bend. Some sections of cobbles have deteriorated beyond the point of safety and repair or have been resurfaced and lost their significance. Other sections are excluded because the route of the race has moved east.

Pacers

Early races were run behind pacers, as were many competitions of the era. The first were other cyclists, on bicycles or tandems. Cars and motorcycles were allowed to pace from 1898. The historian Fer Schroeders says:

In 1898, even cars and motorcycles were allowed to open the road for the competitors. In 1900, the race was within a hair's breadth of disappearing, with only 19 riders at the start. The following year, the organisation therefore decided to allow help only from pacers on bicycles. And in 1910, help from pacers were stopped for good. An option which lifted Paris-Roubaix out of the background and pushed it, in terms of interest, ahead of the prestigious Bordeaux-Paris.

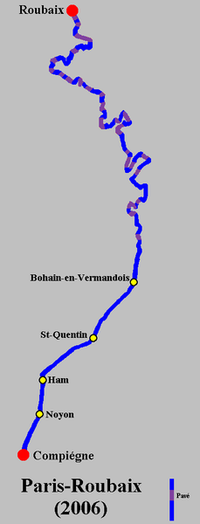

Course

Originally, the race was from Paris to Roubaix, but in 1966 the start moved to Chantilly, 50km north, then in 1977 to Compiègne, 80km north. From Compiègne it now follows a 260km winding route north to Roubaix, hitting the first cobbles after 100 km. During the last 150km the cobbles extend more than 50 km. The race culminates with 750m on the smooth concrete of the large outdoor velodrome in Roubaix. The route is adjusted from year to year as older roads are resurfaced and the organisers seek more cobbles to maintain the character of the race - in 2005, for example, the race included 54.7km of cobbles.

The start

The race has started at numerous places:

- 1896-1897 Porte Maillot, Paris

- 1898-1899: Chatou

- 1900: Saint-Germain

- 1901: Porte Maillot, Paris

- 1902-1913: Chatou

- 1914: Suresnes

- 1919-1928: Suresnes

- 1929-1937: Porte Maillot, Paris

- 1938: Argenteuil

- 1939: Porte Maillot, Paris

- 1943-1965: Saint-Denis

- 1966-1976: Chantilly

- 1977-present Compiègne

The opening kilometres (the départ fictif) have often been a rolling procession. Racing has started further into the ride (départ réel). The start of open racing has been at:

- 1896-1897: Porte Maillot

- 1898-1899: Chatou

- 1900: Saint-Germain

- 1901: Porte Maillot

- 1902-1913: Chatou

- 1914: Suresnes

- 1919: Suresnes

- 1920-1922: Chatou

- 1923-1929: Le Vésinet

- 1930-1938: Argenteuil

- 1939: Le Vésinet

28 cobbled sectors

The organiser, Jean-François Pescheux, grades the cobbles by length, irregularity, the general condition and their position in the race.

In 2008, there were 28 cobbled sections, three considered maximum difficulty. As well as the Trouée d'Arenberg, difficult sections include the 3000m Mons-en-Pévèle (213km) and the 2100 m Carrefour de l'Arbre (244km) — often decisive in the final kilometres.

Section

NumberName Kilometer Length

(in m)Category 28 Troisvilles to Inchy 98 2200

27 Viesly to Quiévy 104 1800

26 Quievy to Saint Python 106,5 3700

25 Saint-Python 111,5 1500

24 Vertain to Saint-Martin-sur-Écaillon 119 2000

23 Capelle-sur-Ecaillon - Le Buat 126 1700

22 Verchain-Maugré - Quérénaing 138 1600

21 Quérénaing - Maing 141 2500

20 Maing - Monchaux-sur-Écaillon 144 1600

19 Haveluy 155,5 2500

18 Trouée d'Arenberg 163,5 2400

17 Wallers - Hélesmes 170 1600

16 Hornaing - Wandignies-Hamage 176,5 3700

15 Warlaing - Brillon 184 2400

14 Tilloy-lez-Marchiennes - Sars-et-Rosières 187,5 2400

Section

NumberName Kilometer Length

(in m)Category 13 Beuvry-la-Forêt - Orchies 194 1400

12 Orchies 199 1700

11 Auchy-lez-Orchies - Bersée 205 1200

10 Mons-en-Pévèle 210,5 3000

9 Mérignies – Pont-à-Marcq 216,5 700

8 Pont Thibaut to Ennevelin 219,5 1400

7 Templeuve l'Epinette

Templeuve Le Moulin de Vertain225

225,5200

500

6 Cysoing - Bourghelles

Bourghelles - Wannehain232

234,51300

1100

5 Camphin-en-Pévèle 239 1800

4 Le Carrefour de l'Arbre 242 2100

3 Gruson 244 1100

2 Hem 251 1400

1 Roubaix 'Espace Charles Crupelandt' 257,5 300

28 - Troisvilles to Inchy

Length - 2,200m

First used 1987. The highest of all the cobbles at 136m. Jean Stablinski memorial on the right. The section drops 900m at two per cent. Students of the Lycée Professionnel Horticole de Raismes planted a hedge in November 2007 to prevent flowing mud. The section climbs gently for the next 900m on to the plateau at 121m. This section is often difficult because of mud. The right-angled left bend towards Inchy is made difficult by mud. The road then drops at 3.2 per cent for 400m.

Cobbles rated

. The cobbles are in fairly good condition except at the end. The second part, after the main road, is always muddy.

27 - Viesly (rue de la chapelle) to Quievy

Length - 1,800m.

First used 1973. This section is slightly descending, dropping evenly from 120m to 100m. It is almost entirely straight, although muddy in parts.

Cobbles rated

. In fairly good condition.

26 - Quievy to Saint Python

Length - 3,700m

First used 1973. This section crosses two regional roads, D113b and D134. This and the section from Hornaing to Wandignies-Hamage is the longest. It rises from 95 to 117m. It begins with a gentle drop, continues with a gentle rise over 600m, then a section almost entirely flat. After being straight, there is then a difficult 90-degree right bend that leads to a 2km uphill drag that riders find exhausting.

Cobbles rated

. Fairly good condition. The regional council relaid the cobbles at the end of the section in 2007. The beautiful farm of Fontaine au Tertre is on the left at the end of the cobbles.

25 - Saint-Python

Length - 1,500m

First used 1973. The start is at 104m, the end at 82m. The road is almost straight, starting with 500 flat metres then a 1km descent to Saint-Python.

Cobbles rated

. In good condition but muddy at first.

24 - Vertain to Saint-Martin-sur-Écaillon

Length - 1,900m plus 100m from which the tar has been removed.

First used 1985. It drops from 105m to 89m in almost a straight line apart from a small bend to the left in the middle.

23 - Capelle sur Ecaillon to Buat

Length - 1,700m.

First used 2005. Rises from 91m to 102m in almost a straight line. It starts with a four per cent drop over 700m, then rises from 66m to 400m at seven per cent, followed by a slow rise of two per cent for 7 500m. The steepest part of the course, ridden by specialists on a 46-tooth ring.

Cobbles rated

. Fairly good state but with strip of tar on the right during the descent.

22 - Verchain-Maugré to Quérénaing

Length - 1,600m.

First used possibly 1974 . Virtually level - 80m to 78m, virtually straight, rising a little and then descending more gently for longer.

Cobbles rated

. In good condition apart from some holes.

21 - Quérénaing to Maing

Length - 2,500m

First used 1996 and used thereafter and always in the same direction. The road is the D59, falling from 85m to 40m in a straight line. It starts with a gentle decline to 72m over 400m, then a slight ride 400m. Then comes a flat stretch followed by a long descent of between 2.5 and 3.8 per cent.

Cobbles rated

. In good condition with a muddy part.

20 - Maing to Monchaux sur Ecaillon

Length - 1,600m.

First used 2001. The road is the D88, rising from 47 to 50m in an almost straight line. It begins with a slight ride of 1,000m, then a slow descent of 600m.

Cobbles rated

. Hard at first, with deep holes, then in excellent condition.

19 - Wallers Haveluy

Length - 2,500m.

First used 2001 and ever since. This is Bernard Hinault section, named in his presence on 28 March 2005 by the municipality. This section is sometimes used by the Quatre Jours de Dunkerque. It starts at 31m and finishes at 34m. It starts with a gentle rise, finishes with a gentle fall.

Cobbles rated

. They are described as average condition but with a lot of mud. The second half is more difficult.

18 - Trouée d'Arenberg

Trouee d'Arenberg - 2008 Paris-Roubaix.

Trouee d'Arenberg - 2008 Paris-Roubaix.The Trouée d'Arenberg, Tranchée d'Arenberg, (Trench of Arenberg), Trouee de Wallers Arenberg, has become the symbol of Paris-Roubaix. Officially 'La Drève des Boules d'Herin', the 2400m of cobbles were laid in the time of Napoleon through the Raismes Forest-Saint-Amand-Wallers, close to Wallers and Valenciennes. The road was proposed for Paris-Roubaix by former professional Jean Stablinski, who had worked in the mine under the woods of Arenberg. The mine closed in 1990 and the passage is now preserved. Although almost 100km from Roubaix, the sector usually proves decisive and as Stablinski said, {{cquote|Paris-Roubaix is not won in Arenberg, but from there the group with the winners is selected. A memorial to him stands at one end of the road.

Introduced in 1968, the passage was closed from 1974 to 1983 by the Office National des Fôrets. Until 1998 the entry to the Arenberg pavé was slightly downhill, leading to a sprint for best position. The route was reversed in 1999 to reduce the speed. This was as a result of Johan Museeuw's crash in 1998 as World Cup leader, which nearly cost his leg to gangrene. In 2005 the Trouée d'Arenberg was left out, organisers saying conditions had deteriorated beyond safety limits. Abandoned mines had caused sections to subside. The regional and local councils spent €250,000 on adding 50cm to restore the original width of three metres and the race continued using it. The Italian rider Filippo Pozzato said after trying the road after its repairs:

It's the true definition of hell. It's very dangerous, especially in the first kilometre when we enter it at more than 60kh. It's unbelievable. The bike goes in all directions. It will be a real spectacle but I don't know if it's really necessary to impose it on us.

In 2001 a French rider, Philippe Gaumont, broke his femur after falling at the start of the Trouée when leading the peloton. He said:

What I went through, only I will ever know. My knee cap completely turned to the right, a ball of blood forming on my leg and the bone that broke, without being able to move my body. And the pain, a pain that I wouldn't wish on anyone. The surgeon placed a big support [un gros matériel] in my leg, because the bone had moved so much. Breaking a femur is always serious in itself but an open break in an athlete of high level going flat out, that tears the muscles. At 180 beats [a minute of the heart], there was a a colossal amount of blood being pumped, which meant my leg was full of blood. I'm just grateful that the artery was untouched.

Gaumont spent a month and a half in bed, unable to move, and was fitted with a 40mm section fixed just above the knee and, to the head of the femur, with a 12mm screw.

Length - 2,400m.

First used 1968. A straight road through the forêt domaniale de Raismes/Saint-Amand/Wallers, dropping slightly at first, then rising. The road is at 25m at the start and 19m at the end.

Cobbles rated

. The cobbles are extremely difficult to ride because of their irregularity. So many fans have taken away cobbles as souvenirs that the Amis de Paris-Roubaix have had to replace them.

17 - Wallers pont Gibus to Hélesmes

-1,600m. - First used 1974 as a replacement for the Trouée. It is straight and level. The start is difficult, the road having partly collapsed, and the stones are irregular.

16 - Hornaing to Wandignies-Hamage

Length - 3,700m.

First used 1983. First used over its entire length 1988. The last 2,900m were used by the Tour de France in 2004. The road is the D130. It falls from 23 to 17m in the shape of an L. It is flat, starting with 800m in a straight line, followed by a turn to the right near two châteaux, then a straight line of 2,900m towards Wandignies-Hamage.

Cobbles rated

. In good condition.

15 - Warlaing to Brillon

Length - 2,400m.

First used 1983. The road is the D81, at 17m at each end, formed in an L. First 400m straight, then a right bend followed by a 2km straight.

Cobbles rated

. In a good condition at first but then with sunken sections.

14 - Tilloy-lez-Marchiennes to Sars-et-Rosières

Length - 2,400m.

First used 1980 but only for the first 1,400m. Used over its entire length from 1982. An L-shaped section of the D158b with two 90-degree right turns and one 90-degree to the left. Starts at 18m and finishes at 19m.

Cobbles rated

. In good condition and regularly maintained. Sometimes muddy because of tractors.

13 - Beuvry-la-Forêt to Orchies

Length - 1,400m.

First used 2007. The section was laid for the race, 700m of cobbles being added to 700 already there. The section was named after Marc Madiot in 2007. It rises slightly for the first half and is then flat.

Cobbles rated

. In a correct condition, although the surface is described as "chaotic" in the first part.

12 - Orchies, chemin des Prières, and chemin des Abattoirs

Length - 1700m.

First used 1980. The 600 last metres were used in the opposite direction for the first time in 1977. The section is L-shaped, the first 1,100m flat and the last 600 slightly uphill.

Cobbles rated

. In a correct state, fairly muddy at first, disjointed in the last 600m.

11 - Auchy-lez-Orchies to Bersee

Length - 1,200m.

First used 1980. The second section, Nouveau Monde, has deteriorated too much to be raced on. The sector rises from 40 to 54m. It is almost flat in the form of a semi-circle.

Cobbles rated

. In correct state, although irregular and difficult in the second half.

10 - Mons-en-Pévèle

Mons-en-Pévèle, cobblestone sector 10, is the 10th section of pavé before the finish. Its 3,000m are rated the hardest level of difficulty, five stars. It is in the municipality of Mons-en-Pévèle. It is one of the key sectors, one of the toughest and within 50km of the finish. It has been used every year since 1978, 2001 excepted. In 1997, 2000, 2002 and 2003, only the first 1,100m were used.

In 2008, Stijn Devolder's attack on this sector was a contribution to the victory of Tom Boonen, his Quick Step team-mate.

Overall the 3,000m rise from 53m at the start to 63m at the end. It begins with a 300m drop of two per cent down to the Ruisseau La Petite Marque at 47m. This is followed by 800m that rise 3m. A 90 degree right-turn to the rue du Blocus introduces a 800m straight that falls 2m and leads to a difficult, muddy, 90-degree left turn to the ruelle Flamande. The final 1,100m of the ruelle Flamande and Chemin de Randonnée Pédèstre rise 16m to Mérignies.

Length - 3,000m

First used 1978. It starts at 53m and finishes at 63m. The first 300m descend at two per cent. Then a right turn at 90 degrees, 800m of flat road, a muddy and difficult left turn at 90 degres and 1,100m of slight rise.

Cobbles rated

. Correct condition for the first 1,100m, then worse, followed by 1,100m on which mud runs down from fields.

9 - Mérignies to Pont à Marcq

Length - 700m.

First used 1981. The road is the rue de la Rosée. It rises from 35 to 37m, almost straight.

Cobbles rated

. Good condition.

8 - Pont Thibaut to Ennevelin

Length - 1,400m.

First used 1978. A flat double L with two 90-degree left turns.

Cobbles rated

. Good condition but muddy for the first 1,000m, then difficult at the end, although work is scheduled to improve it.

7 - Templeuve - Le Moulin de Vertain

- 7 (part one) Templeuve "L"

Length - 200m.

First used 1992. A straight line rising two metres.

Cobbles rated

. Bad at first, then good.

- 7 (part two) Templeuve Le Moulin de Vertain :

Length - 500m.

First used 2002. This section, covered by earth, was dug out for the 100th race. It drops from 38m to 33m in a straight line.

Cobbles rated

. A short section but with cobbles hard to negotiate.

6 - Cysoing to Bourghelles to Wannehain

- (part one) - Cysoing to Bourghelles

Length - 1,400m.

First used 1981. Since 2006 it has included the 300m leading to Bourghelles. Known as the Duclos-Lassalle section, it is level and L-shaped, rising fractionally, descending, rising and then descending again to finish at its original height: 44m.

Cobbles rated

. In good condition for the first 700m, appalling for 300m to the right-hand corner, and good again for the last 300m.

- 6 (part two) Bourghelles to Wannehain

Length - 1,100m.

First used 1992. A slight rise followed by a slight descent.

Cobbles rated

. Fairly good condition at first and then hard to ride in the second half because of the irregular surface. Partly repaved with cobbles from the old road at Péronne-en-Mélantois taken by Paris-Roubaix in the 1950s.

5 - Camphin-en-Pévèle

Length - 1,800m.

First used 1980. L-shaped, falling from 52 to 50m. The right-hand corner in the middle of difficult because of mud.

Cobbles rated

. Fairly disjointed throughout but appalling in the last 300m.

4 - Camphin-en-Pévèle to Carrefour de l'Arbre

Length - 2,100m.

First used 1980.An L-shaped section rising from 48 to 51m. Flat for 1,200m, then a difficult left-hand bend leading to a slight ascent.

Cobbles rated

. Alternate good and bad sections. The section before the corner leading to the restaurant is particularly bad and hard to ride.

3 - Le Carrefour de l'Arbre to Gruson

Frederik Willems and Filippo Pozzato from Team Liquigas on approach the 'Carrefour de l'Arbre' in 2008

Frederik Willems and Filippo Pozzato from Team Liquigas on approach the 'Carrefour de l'Arbre' in 2008Le Carrefour de l'Arbre (or Pavé de Luchin) is the fourth section of pavé before the finish in Roubaix. Its 2.1 km are rated at the hardest level of difficulty, five stars. The crossroads (carrefour) is on open land between Gruson and Camphin-en-Pévèle. The route departs westward from Camphin-en-Pévèle along the rue de Cysoing towards Camphin de l'Arbre. The first half is a series of corners, then along irregular pavé towards Luchin. The second half finishes at the Café de l'Arbre restaurant and has more even pavé. A sharp turn towards Gruson signals the start of sector 3, although this has sometimes been included in sector 4.

The Carrefour de l'Arbre / Pavé de Luchin sector has often proved decisive. This is due to its proximity to Roubaix (15km) and cumulative difficulty, even it is regarded less challenging than the Trouée d'Arenberg. The leader at the completion of the Cafe has a good chance of leading at the velodrome, as Fabian Cancellara did in 2006 and Stuart O'Grady in 2007. As the last area where an attack could prove decisive, it is popular with spectators.

This 1,100m sector, which was first used 1978, drops from 50m to 45m in a straight line. It was also incorporated into stage 3 of the 2004 Tour de France between Waterloo and Wasquehal.

2 - Hem

This 1,400m sector is believed to have been first used 1968 but perhaps as early as the 1950s. A winding section rising from 25m to 30m. Always swept by wind. In 2004, Johann Museeuw suffered a puncture on this stretch, which cost him the chance to contest the sprint for a record equalling fourth victory.

Cobbles rated

. Fairly good state, sometimes disjointed, but the riders take two strips of tar, even if they are pitted by holes that cause frequent punctures.

1 - Roubaix, Espace Charles Crupelandt - The final cobbles

The final stretch of cobbles before the stadium is named after a local rider, Charles Crupelandt, who won in 1912 and 1914. The organiser of the Tour de France, Henri Desgrange, predicted he would win his race. He then went to war. He returned a hero, with the Croix de Guerre. Three years into peace, however, he fell foul of the law and was found guilty in court. The Union Vélocipédique banned him for life, possibly at the urging of rivals in cycling.

Crupelandt raced again but registered with an unofficial cycling association, with which he won national championships in 1922 and 1923. He died in 1955, blind and with both legs amputated.

This 300m sector, dropping from 32m to 27m, is unofficially known as the 'Chemin des Géants,' [Road of the Giants]. It was first used 1996, having been created for the centenary by laying a strip of smooth new cobbles down the centre of the wide boulevard of Avenue Alfred Motte. Dotted among the cobbles are plaques to every race winner, the giants.

Cobbles rated

. Excellent condition.

The finish

The finish until 1914 was on the original track at Croix, where the Parc clinic now stands. There were then various finish points:

- 1896-1914: Rue Verte/route d'Hempempont, Croix, Roubaix

- 1919: avénue de Jussieu, Roubaix, behind the dairy

- 1920-1921: Stadium Jean Dubrulle, Roubaix

- 1922-1928: avénue des Villas (now the avénue Gustave Delory), Roubaix

- 1929: Stade Amédée Prouvost, Wattrelos

- 1930-1934: avénue des Villas, Roubaix

- 1935-1936: Flandres horse track, Marcq

- 1937-1939: avénue Gustave Delory (former avénue des Villas), Roubaix

- 1943-1985: Roubaix Velodrome

- 1986-1988: avenue des Nations-Unies

- 1989-2008: Roubaix Velodrome

The race moved to the current stadium in 1943, and there it has stayed with the exceptions of 1986, 1987 and 1988 when the finish was in the avenue des Nations-Unies, outside the offices of La Redoute, the mail-order company which sponsored the race.

The shower room inside the velodrome is distinctive for the open, three-sided, low-walled concrete stalls, each with a brass plaque to commemorate a winner. These include Peter van Petegem, Eddy Merckx, Roger De Vlaeminck, Rik van Looy and Fausto Coppi.

When I stand in the showers in Roubaix, I actually start the preparation for next year. Tom Boonen, 2004.

A commemorative plaque at 37 avenue Gustave Delory honours Émile Masson Jr., the last to win there.

Bicycles

File:Tafi roubaix.jpgAndrea Tafi's special Paris-Roubaix bicycle, with dual brake levers.Paris-Roubaix presents a technical challenge to riders, team personnel, and equipment. Special frames and wheels are often used. Some have wider tires, cantilever brakes, and dual brake levers. Many teams disperse personnel along the course with spare wheels, equipment and bicycles to help in locations not accessible to the team car.

André Mahé, winner in 1948, said such specialisation is recent:

"[In 1948] We rode the same bikes as the rest of the season. We didn't need to change them because they were much less rigid than modern bikes. The frames moved all over the place. When I attacked, I could feel the bottom bracket swaying underneath me. On the other hand, we had more cobbles. People talk of the amount of cobbles they have now, but when they've finished them they're back on surfaced roads."

Riders have experimented, however. After the second world war many tried wooden rims of the sort used at the start of cycle-racing. Francesco Moser wrapped his handlebars with strips of foam in the 1970s. Gilbert Duclos-Lasalle and Greg LeMond experimented with suspension in their front forks in the 1990s.

Some top riders receive special frames to give more stability and comfort. Different materials make the ride more comfortable. Tom Boonen, used a Time frame with longer wheelbase for the first time in 2005, he won the race that year and has since continued to use a bike with a longer wheelbase. George Hincapie had a frame featuring a 2mm elastomer insert at the top of the seat stays. The manufacturers claimed this took nearly all the shock out of the cobbles. Hincapie's Trek bicycle fared less well in 2006: his aluminum steerer tube snapped with 46km to go, the crash injuring his shoulder.

The bicycle made for Peter van Petegem in 2004 was a Time. The distance from bottom bracket to rear axle was 419mm rather than his normal 403. The distance from the bottom bracket to the front hub was 605mm instead of 600mm. The depth of the front forks was 372mm instead of 367.5mm The forks were spaced to take 28mm tyres. The sprockets were steel rather than alloy and the steerer column was cut 5mm higher than usual to raise the handlebars if needed before the start.

The bad roads cause frequent punctures. A service fleet consisting of four motorcycles and four cars provides spares to riders regardless of team. Yves Hézard of Mavic the equipment company which provides the coverage, said:

Every year we change fewer wheels, because the wheels and tyres are getting better and better. We changed about 20 wheels today. Five years ago, it was much worse - we'd be choosing about a hundred. Tyres are becoming much better than before. So, yes, our job is easier - except that the race generally goes faster now, so we're under a bit more pressure. Every year, there's new types of gears, new aluminium frames, new titanium frames, so it's getting more complex for us to offer neutral service. We have a list in the car of who is riding Mavic or Shimano or Campagnolo; the moment someone gets a flat tyre we need to think of a lot of things at once. Is it a titanium frame or a carbon frame or a steel frame?

Records

- The record of 45.129kmh has been held since 1964 by Holland's Peter Post, but on a different course.

- The record for most victories is by the Belgian Roger De Vlaeminck, who won four times between 1972 and 1977.

- Octave Lapize, Gaston Rebry, Rik van Looy, Eddy Merckx, Francesco Moser, and Johan Museeuw won three times.

- The nations with most victories are Belgium (52) and France (30).

- The record for most races completed is 16 by the Belgian rider Raymond Impanis between 1947 and 1963. Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle completed 15.

- The oldest winner was Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle in 1993 at 38 years and 8 months.

- Eddy Merckx beat Roger De Vlaeminck in 1970 by the largest winning margin, 5 minutes and 21 seconds.

- The closest margin of victory was 1cm, between Planckaert and Steve Bauer in 1990.

- Slowest victory - 12 hours 15 minutes, in 1919 when Henri Pélissier won on roads devastated by World War I.

- Longest victorious break - 222 km, was by the Belgian Dirk De Mol in 1988.

Controversies